An engineer friend of mine, who is the type of man who notices things and has a good humour, gave me a rule of thumb about the early days, "Not all Scotsmen were engineers but all engineers were Scotsmen".

Now, since his and my observations were largely made at Mount Crosby, I suppose we can be forgiven for the embellishment, because there was a distinctly Scottish flavour about the workforce at the Mount Crosby pumping station. From my pay records of 1891 (let’s see you do that with your modern system), I have evidence of the number of Scots that liked steam engines and lived here to be with them.

Joseph Stewart (Chief Engineer) £325/annum

William Thompson (Second Engineer) £250/annum

James Glasgow (Third Engineer) £225/annum

Andrew Simpson (Fireman) £120/annum

George McPhail (Fireman) £120/annum

Eduard King (Fireman) £120/annum

William Mayne (Fireman) £120/annum

Tom Craddock (Fireman) £120/annum

William Bowling (Fireman) £120/annum

James Little (Fireman) £120/annum

Alex McDougall (Blacksmith) One shilling threepence per hour

Samuel McDonald (Striker) Sixpence per hour

Okay, some English, but more than half sound like they appreciate the skirl o’ the bagpipes. Someday, I'll trace their ancestry and find they arose in the land of steam engines and Hogmanay and were the kindred spirits of James Watt, inventor of enough steam engine improvements to start a revolution (truly, no pun intended).

If you are a student of science and humanity, I commend James Watt to you. His engines are simultaneously art and helpful science, and you will be drawn closer to him when you know he was proudest, not of his celebrated steam engines, but for inventing the comparatively invisible "parallel motion" linkage that enabled his engines to be used in pumping stations like ours.

I will try to explain it, but if my words fail, go to the image or the link to see the animation.

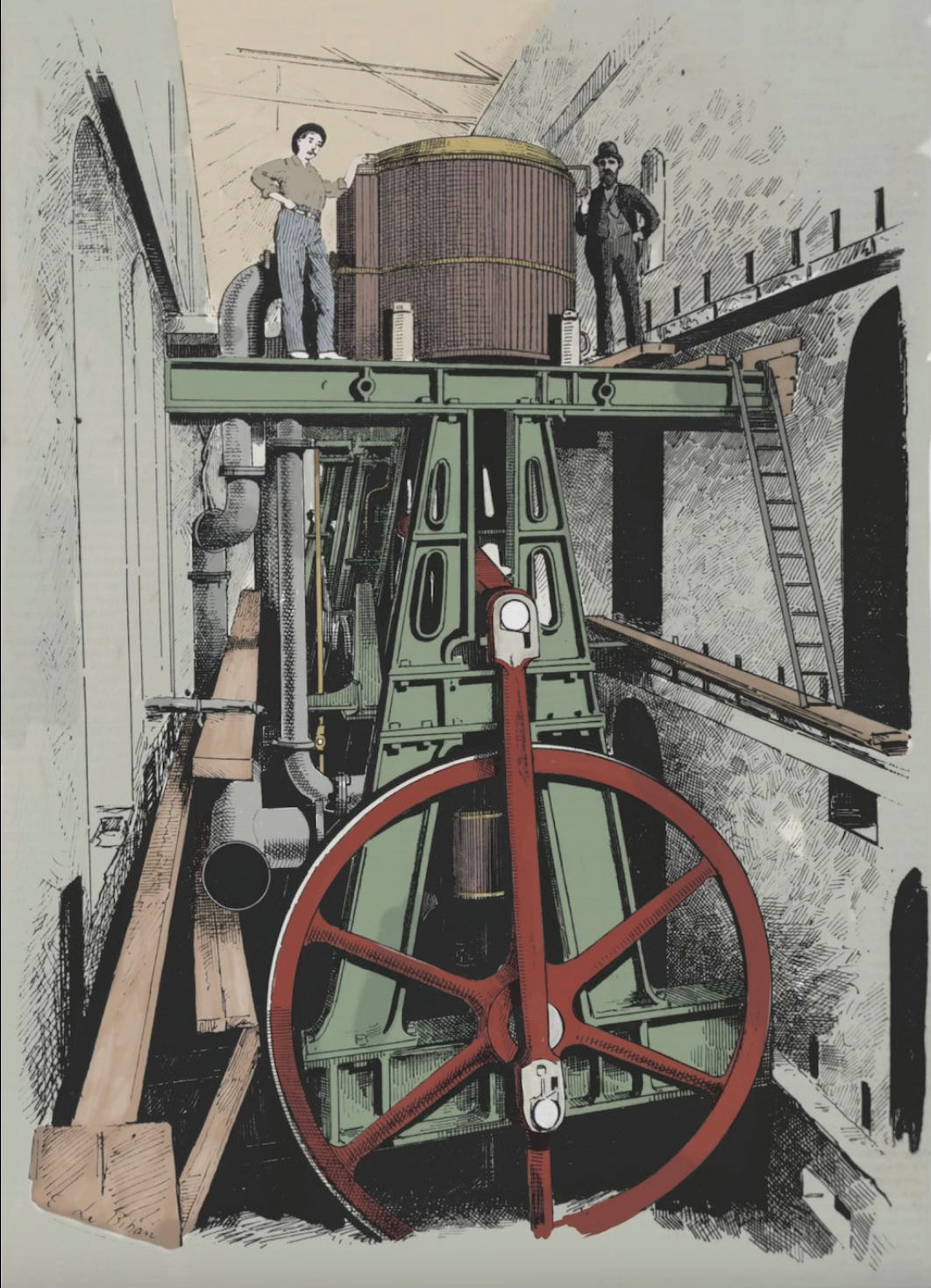

Here’s the problem Watt solved: most water supply or sewerage pumping stations used a form of beam engine – the engine lifts and drops one end of a beam (a bit like a seesaw) while the other end of the beam works the pump plunger up and down to squeeze the water along. This is literally the “water works”.

The piston rod from the engine must move up and down in a straight line but the beam-end moves in an arc. If the piston pushed straight up and down on the arcing beam-end, it would break. The ingenious device that changes the swing of the beam into a straight line is called “Watt’s parallel motion linkage”.

Watts’ linkage worked wonderfully well for steam pumps of the common beam engine type, but Mount Crosby’s great pumps emerged at the technological pinnacle of the steam era (1890-1925). They used another way to straighten things up. They placed the steam engine, with its up and down motion, directly above the pump in the well so that it pushed and pulled directly on the pump plunger located down the well below it.

This had the additional advantage of saving a lot of space, as a result of which, the Mount Crosby pumping station easily accommodated three enormous pumps, which were very tall but had a smaller than average footprint.

This form of direct-acting engine was progressive and cheaper when their maker, Easton and Anderson, offered them to the Brisbane Board of Water Works in 1890. Eventually, they worked brilliantly, but there were severe teething problems at first.

I was forced to write the following note to the Board at the time:

“I have the honour to inform you that since Jany 5th up to date, the representatives of the contractors supplying the engines have had repeated trials of the engines trying to get them to work smoothly and without lifting the girders and all the machinery on top of the girders, and so far without any satisfactory result. The bearings and slides are running fairly, but the engines lift and vibrate very bad, also knocking heavy on both centres.

Those engines knocked so bad that the pumping station walls, windows and my confidence all got cracked at the same time. Eventually, though, I was able to say “satisfactory trials have lately been made, and no mishap occurred except such small breakages as are inseparable from the starting of an extensive pumping plant” – fingers crossed firmly behind back.

Scots loved Watt. Aldous Huxley said a nice thing about him that sums it up. “To us, the moment 8.17am means something - something very important if it happens to be the start time of our daily train. To our ancestors, such an odd eccentric instant was without significance - did not even exist. In inventing the locomotive, Watt and Stephenson were part inventors of time."

To which I can only say “Tooowooot-tooowooot - Start of shift, lads!”

I remain your ob. servant and chief engineer (of the Stewart clan),

Joe Stewart.

References: The Watts Linkage GIF is courtesy of Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parallel_motion_linkage#