Lanz Bulldog Traktor

It wasn’t power or speed that invoked fear of these blue and red Zugmaschines.

A tractor is one of the most helpful things a farmer can have, and I feel pretty certain the makers of the Lanz Bulldog were being a special type of German, industrial, innovative, “helpful” when they sat down to design it.

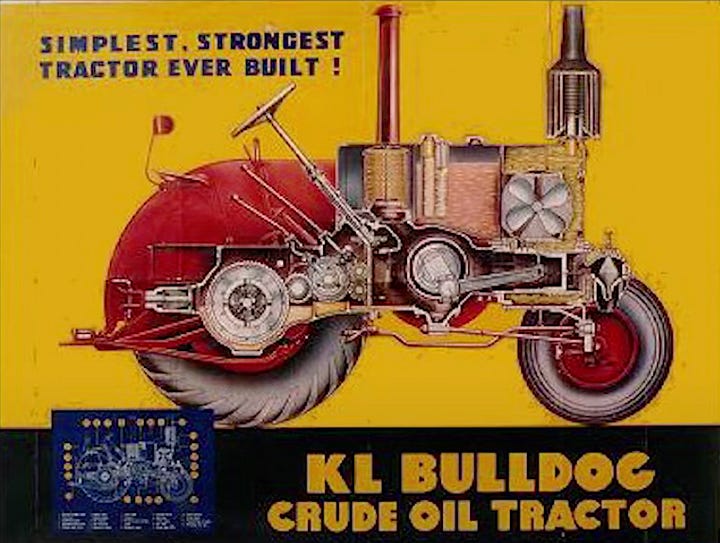

The first Bulldog tractor followed closely on the heels of stationary engines (remember Banger), which themselves followed from steam powered traction engines. None of them were particularly manoeuvrable – most were operated stationary while providing energy for work like threshing, pumping or sawing.

The early Bulldogs (circa 1923) were invented at the cutover between stationary engines and modern tractors, and they never really forgot their uncles. Lanz had been making steam engines since 1878 and even made 22 Zeppelin’s during the First World War (something judiciously removed from their export advertising campaign).

Simultaneously innovative and uncomplicated, I think the unofficial Bulldog motto was probably something like:

Okay, ich habe Angste vor deinem Traktor

[it’s okay to fear your helpful tractor]

They appealed to our farmers because, on the helpful side of the equation, the men of Mannheim designed the Bulldog with a 10.3 litre, single cylinder, two-stroke engine that could run equally well forwards and backwards, and tolerate almost any quality of fuel from the crudest bunker oil, to diesel, to kerosene without complaint.

The ingenious engine design required no carburettor, no electrics and almost no compression. Bulldogs would happily run all day, thud-thudding along at about 160 revolutions per minute, which is literally slow enough to see things going round. Trust me when I say it wasn’t power or speed that invoked fear of these blue and red Zugmaschines.

Those are the counter-intuitive reasons why farmers in our district, as well as many others, chose to buy Bulldogs produced in Germany after each War, notwithstanding the awkward admission that this gear was good. Ted Stumer had one at Stumers Road (nee Tanseys Lane) and there was the one at Summerville’s that got taken from the Karalee riverbank by the extended tongue of Kholo Creek, while employed thud-thudding water into melons.

On the flipside of the “helpful” equation, getting a Bulldog started was a complicated and dangerous business.

Resigned to the fact that the process was going to take at least half an hour, Farmer would fill a petrol blowtorch and pump it up until the flame was blue hot before coupling it to the front of the engine, on a part called the glow head. It’s the glow head that vaporises all that rubbish fuel and starts it burning, so that the squeezing of the piston can fully ignite it and be pushed back down (presto - an engine with no electrics whatsoever). Diesel style, but not a diesel.

While the glow head was heating to a few hundred degrees, Farmer would put 150 turns on the oil pump and grease all the couplings and joints to make sure they worked as the Germans intended (I can hardly believe I wrote that – best you don’t believe it). Once the glow head was almost as hot as the surface of the sun, Farmer would remove the blowtorch to a place where it wouldn’t cause a barn-fire, and get to the real business of rotation. He (no woman could ever be convinced to do this) would decouple the Bulldog’s steering wheel and make use of it as a crank handle by slotting it into a spline on the engine’s flywheel.

That wasn’t even the interesting part - for this is a special engine that can run both ways. Farmer would rock the flywheel back-and-forth like a gorilla until it kicked. Because it might kick forward or it might kick back, the steering wheel crank was dicey to hold and dicey to remove, unlike a normal crank handle that would easily disengage.

The Germans had thought of this, and advised Farmer to forget about using his opposable thumbs (i.e. never use them) or it’s just about certain you’ll lose them.

Just after the thumb injury, Farmer would bump the spinning steering wheel out of its flywheel spline and refit it to the right place, maybe even putting the cover back over the flywheel, but probably not because “I’m just going to have to open that up again next time”.

Almost ready to go, but not so fast, Farmer. Your Bulldog might be running backwards and, that, Farmer, is going to wreck your barn or squash a turkey, if you put it in gear just now.

Hop off the tractor and look carefully at the flywheel to see which way you are going. If it’s backwards (which it almost certainly is), slow the engine down until it almost stops. With some luck it will kick back the other way and you can get going.

If not, the Germans recommend you embrace the Weltschmerz of the situation and thank God you are a farmer with plenty of time on your thumbless hands.

Images:

1. A steam traction engine - to my knowledge no Mount Crosby farmer had anything like the money required to buy one. Image courtesy of Steaming on the Downs Inc.

2. A stationary engine. This one is "Banger", a New Way engine built in Michigan in 1904 and used mainly for sawing and pumping at Burrows Farm, Colledges Crossing before becoming a member of the Hester family. Photograph taken c.1950.

3. Lanz Bulldog Type N (the most common model used in Australia and even manufactured here for a couple of years by Kelly and Lewis in Victoria). Kelly and Lewis called theirs the KL Bulldog, for obvious reasons. Image courtesy of Museum of the Riverina.

* Weltschmerz – literally “world-pain”, a disappointing sense that reality is not living up to its possibilities.